Linear SVM

Large-Margin Problem

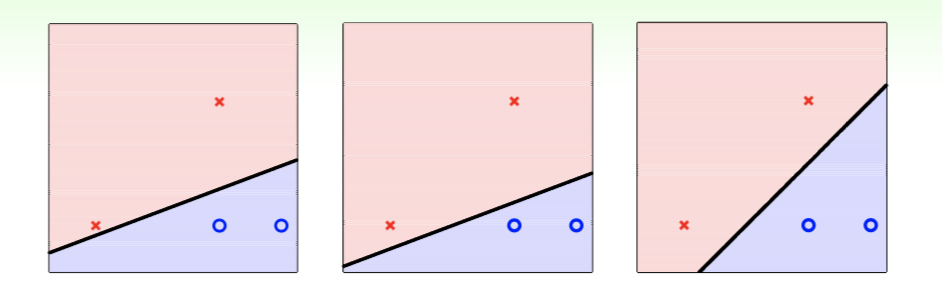

Firstly, we consider 3 linear classifier on the same dataset as follows:

both of them seem performing well but the rightmost one whose hyperplane is farthest from samples is likely to be better.

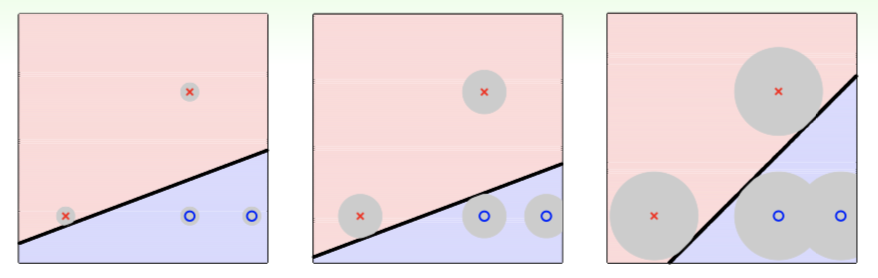

Assume a Gaussian-like noise on future sample $\boldsymbol x \approx \boldsymbol x_n$ in gray area of the following figure:

if $\boldsymbol x_n$ is further from hyperplane, that is, distance between hyperplane and the closest $\boldsymbol x_n$ is greater, then the classifier can tolerate more noise and is more robust to overfitting.

This distance mentioned above is called Margin, then our goal is finding a $\boldsymbol w$ which classifies samples correctly and has the maximum margin at the same time, that is

\[\begin{split} \max_{\boldsymbol w} \ \ &\text{margin}(\boldsymbol w,b) \\[1em] \text{s.t.} \ \ &y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b) > 0, \ n=1,2,...,N \\[1em] &\text{margin}(\boldsymbol w,b)=\min_{n=1,2,...,N}\text{distance}(\boldsymbol x_n, \boldsymbol w, b) \end{split} \tag{9.1}\]where $\boldsymbol x_n=(x_1,x_2,…,x_d)^\text T$, $\boldsymbol w=(w_1,w_2,…,w_d)^\text{T}$, $b$ represents bias and hypothesis $h(\boldsymbol x)=\text{sign}(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x+b)$, which is little different from that in perceptron.

Distance in $(9.1)$ can be written as

\[\text{distance}(\boldsymbol x,\boldsymbol w,b)=\frac{|\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x+b|}{\Vert\boldsymbol w\Vert} \tag{9.2}\]considering for every $n$, $y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)>0$, we have

\[\text{distance}(\boldsymbol x_n,\boldsymbol w,b)=\frac{y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)}{\Vert\boldsymbol w\Vert} \tag{9.3}\]For a specific hyperplane, scaling the coefficients of each items at the same times makes no difference. In the origin model, hyperplane equation is $\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x+b=0$, we assume $\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b=k$. In order to make this form simpler, rewrite hyperplane equation as $\frac{1}{k}(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x+b)=0$, then set $ \tilde{\boldsymbol w}=\frac{1}{k}\boldsymbol w$ and $\tilde b=\frac{1}{k}b$, so we have $\tilde{\boldsymbol w}^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+\tilde b=1$. According to the derivation above, we set

\[\min_{n=1,2,...,N}y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)=1 \tag{9.4}\]then we have $\text{margin}(\boldsymbol w,b)=\frac{1}{\Vert\boldsymbol w\Vert}$ and further we can ensure that for every $n$, $y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b) > 0$ under $(9.4)$.

Therefore, our goal has become

\[\begin{split} \max_{\boldsymbol w,b} \ \ &\frac{1}{\Vert\boldsymbol w\Vert} \\[1em] \text{s.t.} \ \ &\min_{n=1,2,...,N}y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)=1 \end{split} \tag{9.5}\]However, this problem is still not easy enough to solve. Next we consider to replace this constraint with its necessary constraint $y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)\ge1, \ n=1,2,…,N$. To prove the feasibility of this replacement, assume we find the optimal solution $(\boldsymbol w, b)$ when $ y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)>k$ and $k>1$. Then we set $\tilde{\boldsymbol w}=\frac{\boldsymbol w}{k}$ and $\tilde b=\frac{b}{k}$, obviously the new $(\tilde{\boldsymbol w}, \tilde b)$ is more optimal, so the contradiction is found.

After some conversion, we have the particular standard problem

\[\begin{split} \min_{\boldsymbol w,b} \ \ &\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol w \\[1em] \text{s.t.} \ \ &y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)\ge1, \ n=1,2,...,N \end{split} \tag{9.6}\]we call each boundary sample Support Vector, which satisfies $y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)=1$. And from previous derivation, we know the above optimization problem to be solved only depends on these support vectors.

Quadratic Programming

Fortunately, our goal is a quadratic problem which is easy to solve, next we try to convert our goal to a standard form of quadratic programming $\text{QP}(\boldsymbol Q,\boldsymbol p,\boldsymbol A,\boldsymbol c)$:

\[\begin{split} \min_{\boldsymbol u} \ \ &\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol u^\text T\boldsymbol Q\boldsymbol u+\boldsymbol p^\text{T} \boldsymbol u \\[1em] \text{s.t.} \ \ &\boldsymbol a_m^\text T\boldsymbol u \ge c_m, \ m=1,2,...,M \end{split} \tag{9.7}\]Compare this standard form, we have

\[\begin{align} \boldsymbol u &= (b;\boldsymbol w) \\[1em] \boldsymbol Q &= \left(\begin{array}{ccc} 0 & \boldsymbol 0_d^\text T \\ \boldsymbol 0_d & \boldsymbol I_d \end{array}\right) \\[1em] \boldsymbol p &= \boldsymbol 0_{d+1} \\[1em] \boldsymbol a_m^\text T &= y_m(1, \boldsymbol x_n^\text T) \\[1em] c_m &= 1 \\[1em] M &= N \end{align} \tag{9.8}\]then the optimal solution can be obtained by passing these parameters into a function calculating the quadratic programming.

In addition, when the dataset is non-linear separable, we can similarly use a feature transformation $\boldsymbol\Phi$ as it is in linear regression. Only thing we need to do is replace $\boldsymbol x$ in above formula with $\boldsymbol z=\boldsymbol\Phi(\boldsymbol x)$.

Duality

All above derivation we have done is based on the condition where the feature dimension $d$ is not very large, but after feature transformation, the new $\tilde d$ of $\boldsymbol z$ may be quite large or even infinite, then challenges arise at this time. To avoid calculating in a high dimension, we try to find the Dual Problem of original SVM.

One of our key tool is lagrange multiplier which we have mentioned in regularization. From $(9.6)$, we construct the Lagrange function as follows:

\[\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w, \boldsymbol\alpha) = \frac{1}{2}\underbrace{\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol w}_{\text{objective}} + \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_n(\underbrace{1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)}_{\text{constraint}}) \tag{9.9}\]where all $\alpha_n \ge 0$. For each $(b,\boldsymbol w)$ satisfy the constraint in $(9.9)$, we have $1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b) \le 0$, which means $\mathcal L$ gets maximum value only when all $\alpha_n(1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b))=0$. Therefore, we have $\max\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha)=\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol w$. For $(b, \boldsymbol w)$ violate the constraint, the maximum value of $\mathcal L$ can be infinite when $\alpha_n \to \infty$. On this condition, if we take the minimum on $\max\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha)$, that is

\[\min_{b,\boldsymbol w}\left(\max_{\alpha_n \ge 0}\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha) \right) \tag{9.10}\]we can ensure the optimal $(b,\boldsymbol w)$ of $(9.10)$ meet all constraints.

For any fixed $\boldsymbol\alpha’$ with all $\alpha_n’ \ge 0$, we have

\[\max_{\alpha_n \ge 0}\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha) \ge \mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha') \tag{9.11}\]and then

\[\min_{b,\boldsymbol w}\left(\max_{\alpha_n \ge 0}\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha) \right) \ge \min_{b,\boldsymbol w}\mathcal L(b, \boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha') \tag{9.12}\]considering the arbitrariness of $\boldsymbol\alpha’$, $(9.12)$ established for all $\boldsymbol\alpha$, so we further have

\[\min_{b,\boldsymbol w}\left(\max_{\alpha_n \ge 0}\mathcal L(b,\boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha) \right) \ge \max_{\alpha_n\ge0}\left(\min_{b,\boldsymbol w}\mathcal L(b, \boldsymbol w,\boldsymbol\alpha)\right) \tag{9.13}\]which we call Lagrange Dual Problem. if the dual problem solved, we get a lower bound of the origin problem. And in this problem it is a Strong Duality which means both sides of the inequality is exactly equivalent. Then our goal has become

\[\max_{\alpha_n\ge0} \ \min_{b,\boldsymbol w}\left(\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol w + \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_n(1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)\right) \tag{9.14}\]Firstly the inner problem, set $\nabla_b\mathcal L=0$, we get

\[\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n=0\tag{9.15}\]then our goal is reduced to

\[\max_{\alpha_n\ge0} \ \min_{\boldsymbol w}\left(\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol w + \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_n(1-y_n\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n)\right) \tag{9.16}\]next set $\nabla_{\boldsymbol w}\mathcal L=0$, we get

\[\boldsymbol w=\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n\boldsymbol x_n \tag{9.17}\]rewrite our goal

\[\begin{split} &\max_{\alpha_n\ge0} \left(-\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol w + \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_n\right) \\[1em] =&\max_{\alpha_n\ge0} \left(-\frac{1}{2}\Vert\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n\boldsymbol x_n\Vert^2 + \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_n\right) \\[1em] =& \min_{\alpha_n\ge0} \left(\frac{1}{2}\Vert\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n\boldsymbol x_n\Vert^2 - \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_n\right) \\[1em] \end{split} \tag{9.18}\]then we have standard dual SVM

\[\begin{split} &\min_{\boldsymbol \alpha} \ \frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=1}^N\sum_{m=1}^N\alpha_n\alpha_my_ny_m\boldsymbol x_n^\text T\boldsymbol x_m - \sum_{n=1}^N \alpha_n \\[1em] &\text{s.t.} \begin{cases} \alpha_n\ge0 \\[1em] \alpha_n(1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b))=0 \\[1em] \sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n=0 \\[1em] \boldsymbol w=\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n\boldsymbol x_n \end{cases} \end{split} \tag{9.19}\]constraints listed above is called KKT Conditions. Dual SVM is also a quadratic programming, we can get the optimal $\boldsymbol\alpha$ by rewriting the object and constrints to the standard form and then passing it into the QP function. Aftering get the optimal $\boldsymbol\alpha$, we can easily get the optimal $\boldsymbol w$ using constraint $(9.17)$, and according to $\alpha_n(1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b))=0$, if we find a $\alpha_n$ grater than $0$, then $b$ can be obtained by solving $1-y_n(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_n+b)=0$. From this we find the model is only determined by the support vector.

Kernel

When we use feature transformation $\boldsymbol z = \boldsymbol\Phi(\boldsymbol x)$ to solve the problem in a high space $\tilde d$, then the complexity to calculate $\boldsymbol z_n^\text T\boldsymbol z_m$ is $O(\tilde d)$. It costs a lot when $\tilde d$ is quite large. We are tring to find a method to get rid of the effect of $\tilde d$.

Firstly consider a $2$nd order polynomial transform

\[\boldsymbol\Phi_2(\boldsymbol x)=(1,x_1,x_2,...,x_d,x_1^2,x_1x_2,...,x_2x_1,x_2^2,x_2x_3,...,x_2x_d,...,x_d^2) \tag{9.20}\]then

\[\begin{split} \boldsymbol\Phi_2^\text T(\boldsymbol x)\boldsymbol\Phi_2(\boldsymbol x')&=1+\sum_{i=1}^dx_ix_i'+\sum_{i=1}^d\sum_{j=1}^dx_ix_jx_i'x_j' \\[1em] &=1+\sum_{i=1}^dx_ix_i'+\sum_{i=1}^dx_ix_i'\sum_{j=1}^dx_jx_j' \\[1em] &=1+\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x'+(\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x')(\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x') \end{split} \tag{9.21}\]The complexity of calculating inner product in $\boldsymbol z$ space is $O(d^2)$, but through $(9.21)$, we reduced it to $O(d)$. Record $K_{\boldsymbol\Phi}(\boldsymbol x, \boldsymbol x’)=\boldsymbol\Phi(\boldsymbol x)^\text T\boldsymbol\Phi(\boldsymbol x’)$, called Kernel Function.

With kernel function, the optimization target can be rewrote as

\[\min_{\boldsymbol\alpha} \ \frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=1}^N\sum_{m=1}^N\alpha_n\alpha_my_ny_mK(\boldsymbol x_n,\boldsymbol x_m) - \sum_{n=1}^N \alpha_n \tag{9.22}\]as mentioned above, we get $b=y_s-\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x_s$ from the support vector, another hand we have $\boldsymbol w=\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n\boldsymbol x_n $ in $(9.17)$, therefore we rewrite $b$ as following form with kernel:

\[\begin{split} b &= y_s-\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_n\boldsymbol x_n^\text T\boldsymbol x_s \\[1em] &= y_s-\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_nK(\boldsymbol x_n,\boldsymbol x_s) \end{split} \tag{9.23}\]besides, the final hypothesis of SVM is $g_\text{SVM}(\boldsymbol x)=\text{sign}(\boldsymbol w^\text T\boldsymbol x+b)$, also we can rewrite it with $(9.17)$ and kernel:

\[g_\text{SVM}(\boldsymbol x)=\text{sign}\left(\sum_{n=1}^N\alpha_ny_nK(\boldsymbol x_n,\boldsymbol x)+b\right) \tag{9.24}\]Polynomial Kernel

Consider a general $2$nd order polynomial transform as follows

\[\boldsymbol\Phi_2(\boldsymbol x)=(1,x_1,x_2,...,x_d,x_1^2,x_2^2,...,x_d^2) \tag{9.25}\]the kernel function is $K_2(\boldsymbol x,\boldsymbol x’)=1+\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x’+(\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x’)(\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x’)$, if we set

\[\boldsymbol\Phi_2(\boldsymbol x)=(1,\sqrt{2\gamma} x_1,\sqrt{2\gamma}x_2,...,\sqrt{2\gamma}x_d,\gamma x_1^2,\gamma x_2^2,...,\gamma x_d^2) \tag{9.26}\]then we have a simple form of kernel

\[\begin{split} K_2(\boldsymbol x,\boldsymbol x')&=1+2\gamma \boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x'+\gamma^2(\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x')(\boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x') \\[1em] &=(1+\gamma \boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x')^2 \end{split} \tag{9.27}\]further, we define the General Polynomial Kernel shaped like

\[K_Q(\boldsymbol x,\boldsymbol x')=(\zeta+\gamma \boldsymbol x^\text T\boldsymbol x)^Q \tag{9.28}\]where $\zeta \ge 0$ and $\gamma > 0$.

Gaussian Kernel

We can use Gaussian function to implement mapping to infinite-dim space, and the Gaussian Kernel in this process is defined as

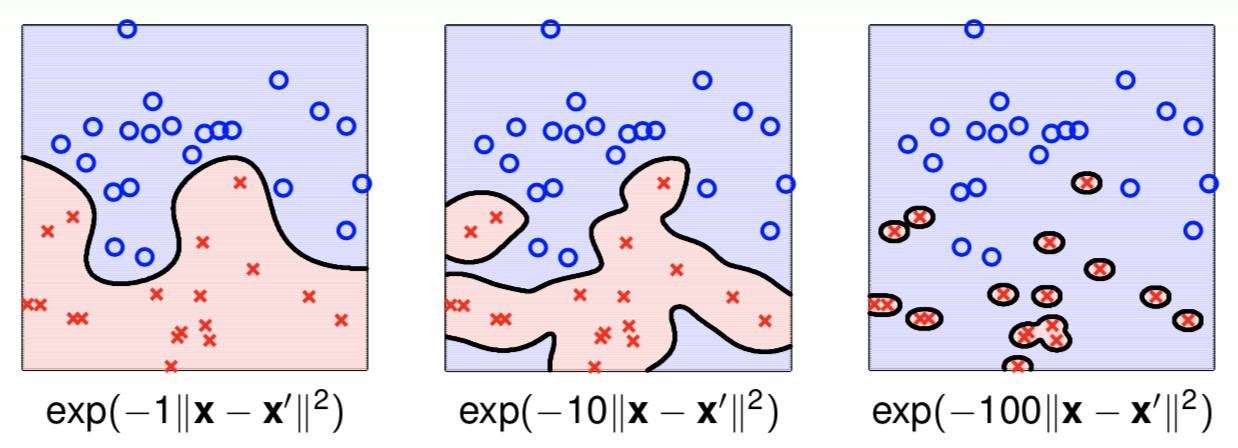

\[K(\boldsymbol x,\boldsymbol x')=\exp\left(-\gamma\Vert\boldsymbol x-\boldsymbol x'\Vert^2\right) \tag{9.29}\]Next we consider different choices of $\gamma$

obviously, we find that a too large $\gamma$ results in overfit. Therefore, a relatively small $\gamma$ is recommendable.

Mercer’s Condition

Sufficient and necessary conditions for valid kernel:

Symmetric

Let $k_{ij}=K(x_i,x_j)$, then we have

\[\begin{split}\\ \boldsymbol K &= \left( \begin{array}{ccc} \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_1)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_1) & \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_1)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_2) & \cdots & \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_1)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_N) \\[1em] \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_2)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_1) & \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_2)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_2) & \cdots & \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_2)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_N) \\[1em] \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\[1em] \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_N)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_1) & \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_N)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_2) & \cdots & \boldsymbol\Phi^\text T(x_N)\boldsymbol\Phi(x_N) \end{array}\right) \\[1em] &= (\boldsymbol z_1,\boldsymbol z_2,...,\boldsymbol z_N)^\text T (\boldsymbol z_1,\boldsymbol z_2,...,\boldsymbol z_N) \\[1em] &= \boldsymbol Z\boldsymbol Z^\text T \end{split} \tag{9.30}\]the matrix $\boldsymbol K$ must always be positive semi-definite.